(Part Three of this essay can be found here. Parts Four and Five can be found here.)

ONE: 1997

I had told A. the story of my son Brennan, how it is that his unrelenting epilepsy and severe learning disabilities have always reminded me of my father Hank's infirmities, who had himself died in the middle of an epileptic seizure in January 1971. Hank's illness had sickened his mind as well in the last ten years of his life. His speech had been reduced to the simplest of expressions. He said the same things over and over, with occasional long pauses between utterances, and so was very similar to how Brennan is now.

Their epilepsies are not related genetically. My father's seizures were caused by a slow-growing brain tumor, while my son's have no demonstrable cause of any kind. Nonetheless, the symptoms of their epilepsies are, to me, almost alarmingly similar, as are the two men themselves. They look so much alike that my son appears to me as a kind of copy of my father, the way my father appeared as a young man in his twenties in old photos. And they are most alike in how they are afflicted. The leaden talk. The long monologues. The repetition. I am frustrated by my son in the same ways I was frustrated by my father. Angered by them similarly. Crazed by them similarly. And I recognize how important I am to my son, and how my father so insistently sought my approval by raining down so much approval on me. The fact that neither man really knows much about me, or could know much, occasionally deadens my feelings for myself and for what I feel I must do to understand the two of them properly.

When I speak with Brennan now, twenty-six years after the death of my father, I realize that he was born less than a year after my father died, and that when he is attempting to tell me a personal anecdote of some kind—his personal story—it is then that he sounds most like my father.

I tell A. all this and, silent in the gloom of the car, she looks out into the surrounding darkness.

"Well, it's clear to me," she says abruptly. "Your son is your father, that's all, come back to tell you what you missed."

"What did I miss?"

"The truth about yourself."

__

TWO: 1997

When he was very small, my son Brennan loved to run up the trails toward the Children's Grove, a section of great monument redwoods in the deep forest forty miles south of Eureka, California. He was quick and bright, his then-blonde hair a fluff of light bounding through the sword ferns and clover. He hid from us behind a tree, and jumped out, as though cloven- hoofed, to frighten us. It was a constant game, and he played it over and over. As long as we wanted to be frightened, he wanted to frighten us.

In that forest, such creatures abound, though usually they are only imagined as they shimmer in the late sunlight faraway in the trees. They can be seen in winter as well, in the cold runoff from a sodden storm or in the waver of the five-finger ferns tapped by rain from above. Such a forest engenders spirits like Brennan, and he ran about through the groves, his laughter sharp in the dark afternoon silence.

The trees themselves, so famous, barely moved. The unnerving thing about them, for me, is not their size, though they are the biggest in the world. It is that they are so straight. They grow without any sense of doubt. They suffer no infirmities. So, it is easy to be frightened by them.

There is, for example, the "widow-maker," a specific danger of which there is plenty of evidence in the groves. A straight branch that has been knocked free by the movement of the trees against each other, it falls to the ground like an arrow. Frequently it enters the ground with such force that the still-green frond of the branch stands up like a newborn tree. But really it's an instrument of death, should it fall on the hapless tourist or unsuspecting forest ranger making his way whistling through the afternoon. I have always expected to find a widow-maker driven through the heart of some passerby, his tongue lolling and black, like that of Lon Chaney, Jr. lying in his coffin.

But that's a small matter compared to what would happen to you if an entire tree fell on you, and entire trees frequently fall in these forests. The root systems are shallow, and spread out from a short core. The trees can be as high as three hundred feet. So, when one is encountered fallen down in the forest, it seems to disappear far into the distance like a tremendous, bark-laden monster. With time, the fallen tree itself becomes covered with ferns and clover-like moss from which Celtic mists seem to rise on summer mornings. The dead root system rises up like a star, crusted with red earth and tentacles all around the outer edges. The root system of a fallen redwood can itself rise up thirty feet from the ground.

Cathleen and I and her parents would go on walks through the groves with various of her little cousins, nephews, and nieces. Brennan and the other kids would play the game, running up ahead in order to hide from us and scare us.

On one particular day, we were walking with Cathleen' s nephew Chuckie and a teenage friend of his, a boy named Chris. The forest was quite warm, it being the middle of August. We meandered through the trees, following the trail over a short hill, past several redwoods, and along the south fork of the Eel River. It was a lighthearted afternoon walk, spent in one of the wondrous forests of the world.

Chris decided that he wanted to climb up onto a fallen tree. He took Brennan with him, and the two of them disappeared the length of the tree, looking for a way up on to the trunk. They reappeared after several minutes, two sailors on the deck of a sailing ship.

Brennan waved at us and threatened to jump. He stood at the very top of the root system, with Chris, looking down at us. I could feel the excitement in him, the sense of derring-do that laces a child with the certainty that his parents are watching him, that he has all their attention, and that nothing bad can happen to him now.

And then Brennan fell, in a sudden, spasmodic seizure.

"Chris! Grab him!" Cathleen yelled, as Brennan pitched forward, stiffened by the epileptic attack. "Grab him now!"

Chris took the tail of Brennan' s shirt between his hands, arresting the fall. Then, quite gracefully, as though they were two dancers on the stage, he grabbed Brennan by the stomach and lifted him onto the flat surface of the tree trunk, laying him down on his back. I could see only Brennan' s hands and arms, extended into the air, vibrating in the seizure's rush.

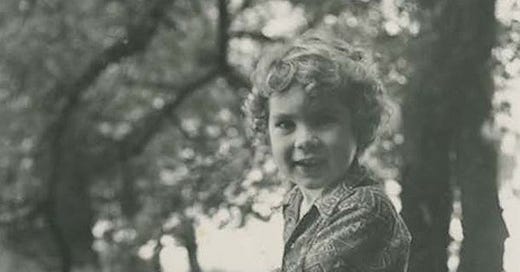

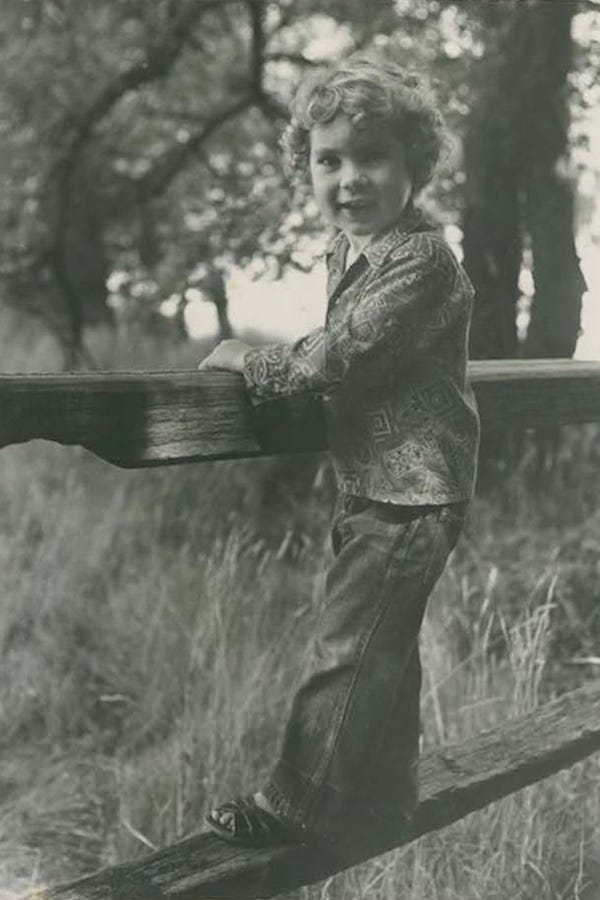

We don't have many photographs of Brennan from those years, and I believe that that is because he was so ill. But in one of them, the shadow falling across the redwood fence on which he's playing gives an impression of vernal softness, as though the afternoon were simple, pleasant, a lark in the woods. Which it was, and Brennan, then just three, was the one most responsible for that.

In the photo, he's playing on a grape-stake fence in the shade of an oak tree, summer 1975. We were still a family then and, as during every summer year after year, we were at Englewood, a ranch owned by Cathleen' s family, in the Redwood National Forest south of Eureka, a few miles north of the Children's Grove.

The ranch was the kind of place I would have thought imaginable only in my imagination. But there it was, every year, five houses, each representing a different clan-like splinter of the Daly family, each one at just enough distance from the others to make any neighborly contact unlikely or, more to the point, unnecessary. The houses were surrounded by apple orchards, Douglas firs, redwoods, plum trees and grasses, all moving about in the summer afternoon wind, so that we would be lulled into a kind of floating oblivion every day after lunch. There were bridge games and swimming in the pool, horseback riding and visits to the one-room schoolhouse on the neighboring ranch, and walks to the Old Orchard with Brennan, like the one this afternoon, the purpose of which was to gather wildflowers for that evening's dinner table centerpiece.

Brennan was, as most people said who ever saw him then, an angel. Even at three years old, his nascent kindliness showed in the way he offered a fistful of crushed blackberries to his favorite aunt Michaela, or held a cat in his lap. At the supermarket, we were forever approached by other customers, usually women, to be told that they had never seen such a handsome boy. Such beautiful hair, they said. So sweet.

This kindness of his shows in the photo as well…in the European touch of the scuffed sandal, appropriate to his having been born in Paris, and in the patterned cotton shirt that I remember was faded red and quite manly, especially when worn with his dust- splotched jeans. He looks at the camera with obvious enjoyment of the moment. He doesn't question much. He lives a life the way children are supposed to. He's loved. His eyes soften with the attention given to him by his mother, who is taking the picture while I stand at her shoulder.

That he undergoes many enormous seizures a day does not matter at this moment. He may fall from the fence in a paralysis a half minute later, to kick dust about, his eyes searching the trees in a manic clutch, his face gray and twitching as the seizure's current runs through him. But for now he is the Brennan we had hoped for, simply enjoying the fence, the warm afternoon, and the affection of his parents.

There have been so many seizures over the years that they run into each other in my memory. Brennan fell forward. He fell backward. He fell in every way possible. But, like the attack in the Children's Grove, particular ones stand out.

He once went into a seizure as I was feeding him. He was in a highchair, and I had just popped a blueberry into his mouth. His teeth clamped down on my finger, and I had to wait a minute or so, clenching my own teeth, until he was released. The bleeding teeth marks on my index finger eventually healed, then turned blue, like bruises, finally disappearing after two or three weeks.

When Brennan was about five, we were standing at the corner of Mason and Columbus in San Francisco, down the hill from our apartment. It was a very cold fall morning, and we were bundled up against the wind. We were awaiting the cable car. I was looking down the hill on Columbus for the trolley when I heard a thump, like a dropped melon breaking against the ground. Brennan had fallen face down to the sidewalk. His arms were at his sides. He writhed, jerkily, and his face was ground into the cement, smudging it with smears of blood.

Another time, a few weeks later, we were riding on the cable car, the California Street car. My mother was with us, and was seated on the bench inside. I stood before her, holding to a leather strap. Brennan was in my free arm, saddled on my hip, and I recall that I was looking out the window at Grace Cathedral.

He entered a seizure, a very violent one. His entire body stiffened and his arms rose up, his face turning gray and twitching. I called to my mother, and then saw that the woman sitting next to her was riveted with terror. She was dressed in a red wool coat and a scarf. Brennan' s face took on the pale, phantasm-like color of death. His eyes were contorted, turned up and inward. The woman's glance at me was as contorted as his face, though her look came simply from fear. Brennan' s body stiffened, unresponsive to my murmurings of comfort. He was lost in the seizure.

The same happened one morning in the Caffé Trieste on Vallejo Street. He and I were seated on the window bench to the left as you enter the cafe. I was reading, and his convulsion caused his legs to straighten, his arms to flail before him. By then (he was about six) I had become quite accustomed to the attacks, so I continued reading. It was a Jane Austen novel. Emma, I think. The seizure lasted half a minute, and, as I looked up, I noticed the man across the table from me, a poet of some sort, judging from the pencil manuscript before him. There was an ashtray piled high with his exhausted cigarette butts. He was aghast, his yellowed eyes terrified by Brennan' s gyrations. I checked Brennan over. He was sound asleep, immediately so, which is normal for the post-seizure half-hour. I turned back to Emma, too angered by the moment to say anything comforting to the beatnik across the way.

But later I wondered, was this man shocked by the seizure itself? Or did he find my interest in the book a kind of callous betrayal of my son's illness? Had I arrived at war-weariness? Was I heartless, a father who ignored his son because he was ill?

Or was I simply accustomed to the lightning?

When he was a teenager, Brennan had a seizure in front of a store on Market Street in San Francisco, and his companion, a girl from his school, panicked and called an ambulance. I had learned from other epileptics that this event is embarrassing, and unfortunately quite frequent. It's embarrassing because the ambulance usually is not necessary, since the seizure will end after a few minutes, and the epileptic will recover on his or her own. However, a manic siren and the feverish ceremony of rescue by the para-medics draws a crowd. So that, when the epileptic finally emerges from his seizure, usually not knowing what has happened, he is on his back on the cement, surrounded by horrified onlookers.

Knowing this, I commiserated with Brennan after he had returned home from the hospital, saying I was sorry he had to be carried away in an ambulance, in such an aggravating way. He responded that "Gee, Dad, I thought it was kind of fun."

Last summer, he had his first seizure in a swimming pool. His cousin André was with him, and saved him from drowning.

Brennan has had so many seizures that it has been difficult to tell whether they ever actually end. Sometimes it has felt like he is having just one seizure, all the time, with quiescent moments during the general storm. You try to protect your son, to keep his writhing from doing him damage. In a seizure, he moves as though an iron burst of electricity has entered him and plunged through his body, head to foot. He is rigid and shaking, and as I watch, I can imagine what it feels like, the surge of the electric bolt charging his muscles

But this is writerly excess, poetic license. Apparently, he feels nothing, although to see the aftermath of one of these attacks, in which he is entirely lethargic, cannot speak, and looks at you through a watery glaze of incomprehension, you would think that some sort of angry wrath has seized him and wrung him of all his life, except for the will to stay alive. Often I cradle his head in my hands, imagining that I can feel the surge tearing through his mind.

Brennan's seizures as a young child were worse than those later. At least it seems that way to me now. They were very frequent (about eight a day) and quite violent. But he was small then, and we could hold him close and caress him, so that often the seizures went unnoticed by anyone else. We could always feel them, though, because his child musculature would tighten like ropes.

The worst of it for me was that I was so helpless in any effort to give him aid. My son collapsed in a writhing heap and twitched in some kind of seeming possession. He retreated from the world, and I could simply stand and watch. Or lie down with him and watch. Caress him, take his hand, kiss him…and watch. There was nothing I could do. I was paralyzed myself, and could only wait for the moment of his release, unable to help him. He was alone, floating through his seizure, voyaging through a terrible half-minute of electrification.

At this writing in 1997, Brennan is twenty-six years old. He has had about twenty thousand such attacks in his life.

There is a similar familial kindness in the photograph of my father that was taken in the summer of 1928 by his brother Gene, in the Mojave Desert in California. The fact is that, in this photo, my father Hank looks like my son Brennan now.

Hank sits on the hood of a Ford Model A, a shotgun held tight in his two fists. He looks like he doesn't really know how to hold the gun. He told me about this day many times, how he and his brother and some friends went out to the Mojave to hunt jackrabbits. While Gene drove, Hank sat on the hood, a leg wrapped about a headlamp. They drove cross-country, the car bounding wildly through sage and ruts. When someone spotted a jackrabbit, Hank took aim and fired. I don't believe a rabbit ever lost its life during one of these hunts, and I can imagine the bolt of pellets flying off into some dry gully, there to terrify a roadrunner at rest or a family of gophers airing themselves in the desert morning.

The smile is what gives my father's vulnerability away. The photo is bright with enjoyment and hope. He never victimized anyone knowingly. He was conservative, kind, unwilling to bother people with his problems. Indeed, now that he's been dead for a quarter century, I find it difficult to imagine his being adept at such a destructive act as aiming a shotgun at anything.

He would go on to a career at Montgomery Ward, labors that were not very well understood by me, especially when I went to Berkeley in the 1960s and learned from the pamphlets handed out in Sproul Plaza that a life like that spent by my father — pushing the "hard lines," pots, pans, and hardware, from Oakland to Boise to Spokane — made him a simple Tool of The State. He was that worst of all possible villains, a businessman. Worse, a salesman. No matter that he did such things for love of his family, or that he himself had not been able to finish his education at the University of Arizona because of the Depression of 1929. He had had to go to work to support his younger brother and sister after their parents had died.

My doctrinaire, breezy bohemianism was just barely tolerated. The beard I had in the 60s — a laughable fuzz that appeared to be pasted to my cheeks — was more than my father could bear. But, although it was the single most obvious hint about the truth of my life, he chose not to publicly notice it. He said nothing about my beard, as though it were a secret indiscretion that he did not wish to acknowledge.

It was my father's unwillingness to bother others with his difficulties that was our undoing as father and son. My father was ill for the last ten years of his life with a brain tumor that made him prematurely senile. He fell into patterns of repeated language, so that the opinions he had fashioned from the ruin of the Great Depression were stated over and over, usually verbatim. They were often negative opinions, in which minorities were ill-treated, political demonstrators excoriated, dreamy endeavors misunderstood. Dreamy endeavors like my own, which I did not share with him because, I felt, he would never understand them. The poetry I wrote, for example, my first effort as a writer.

But there was no apparent fire in his outrage. My father had been enclosed and made self-protective by the economic troubles of his youth. He was a mild man. So he did not rage and lurch. His anger was quiet.

The repetition was caused by his tumor, which grew, amoeba-like and inexorable for decades. It pushed his brain aside. Finally, it addled him, so that his conservatism took on an extra dimension that I now realize was illness.

The worst was when I came home from Berkeley every few months for a visit. After dinner and television, my mother and sister would go to bed, and I would sit up with my father. He would take out a cigarette, a rare indulgence for him, and we would shoot the breeze.

He was in his late fifties, and his curly hair was graying. He always kept it very well groomed, and, of course, short. It was part of his conservative ideal for himself that his appearance remain always the same. So, I never saw him when he was not neat. He sat in an easy chair, and held the cigarette away from him, down at his side. There was a delicacy to the gesture, as though he did not want the smoke to get in his eyes. These conversations seemed dictated to him by something outside of him. He was a stuck record. As I sat through them one after another over the years, I was able to memorize them.

First, he spelled out what he had not had as a youth.

"You know, my brothers Gene and Jack went off on their own. So, I never had a real family. Jack was trying to get into the movies. And Gene was at USC, playing football with John Wayne. There wasn't much…much family life."

I remained silent. Soon, there would be his college days, and baseball.

"And when I went to Arizona, on a baseball scholarship…" My father leaned forward and brought the cigarette to his lips. His glasses gleamed in the reflected light from the lamp to my right. He crossed his legs. "You knew I had a scholarship, didn't you?"

I nodded. The scholarship had not lasted, ruined by the stock market crash.

"Yes, it was a shame. I lost the scholarship. Gosh…1929, imagine that! So long ago. Funds dried up, no money. I had to go back to…" He shook his head. "To Glendale." He surveyed his hands, open before him on his lap. "You know, I always wanted to be...” He sighed, smiling to himself. He had studied Spanish in school, and still enjoyed speaking it when he could. "To be a Spanish teacher. But I guess it just wasn't to be."

Then my father would begin a long description of what made him happy.

There were my older brother Mike and younger sister Kate and their obvious abilities in school. Kate especially was a star, with her very quick smile, her obvious brains, her contemplative manner and her superior golf game. He loved her, I believe, more than he loved anyone else in his life. There were as well my mother and her family, a large, argumentative, and humorous group of Irish-American Catholics. "You know, when you're like me, out here in left field, to see them laugh at each other...the way they make fun of each other...."

At this point in the conversation, I would begin to feel a kind of painful impatience, because I knew that my father did not think much of himself, by comparison to everyone else. He had lost his mother at the age of ten, and had never been close to his father. My mother's family provided a refuge for him, though he never seemed to feel that he had been accepted as a member of it. So I would become impatient with him, because his assumption that he was outside the pale actually made him so. He was an outsider, out in left field, as he said so very often, a stranger. Sitting in the easy chair, he appeared entirely isolated. The light from the single table lamp seemed to fall only on him, dimly so, leaving the rest of the room, including me, in darkness.

The most immediate memory I have of those conversations, sadly, is the one in which I could predict, several sentences ahead, several minutes ahead, what my father would say. And then there would be my disappointment—No. Finally, after so many such conversations, my disgust—as, indeed, he made the utterances word for word. I might try to deflect the subject material, to change it to something else. But he always came back immediately to what he wished to say. I memorized whole conversations.

He would praise me without criticism, as the epitome of what he had wished to be…bright, humorous, with fine grades and a bright future.

The reader may wonder how this could be difficult for me. Few of my men friends have ever been so well regarded by their fathers. The trouble was that my father did not really know that I was skipping class and hanging out. I was barely making it through the university, and was selling jewelry from a stand in front of Cody's Books on Telegraph Avenue. I had no plans. I drank beer and discovered my love of a social life. I went to the movies at the Telegraph Avenue Cinema, where my landlady was the charwoman. She got free tickets, which she gave to me. I did read a great deal. Hubert Selby, Jr. William Burroughs. Thomas Pynchon. Baudelaire. Kerouac. And, of course, Allen Ginsberg.

And I made fun of my father to myself, laughing at his inane observations, the unquestioned value he saw in my efforts at Berkeley, and his reactionary stories, over and over.

It was only years later that I concluded that his repetition was caused by the same tumor that killed him. I had had no idea that he was so ill, even though once, years before, when I was seventeen, he had been taken away in an ambulance, having suffered a major seizure in the middle of the night. None of us children was told that my father had had a seizure that night. Nor were we told that he had been suffering such violent deep-sleep seizures for a decade. Our parents did not want to burden us, as the saying went, with their troubles. We were told that Dad had been taken with a spell of some sort, and when he came home a few days later, everything went back to normal. He worked. We went to school, and as time went by, he repeated himself more and more often. He puttered about the house incessantly. He grew increasingly strange. He listened to the same records he had listened to for years, over and over. He retreated, the repetition incessant.

My father died during another seizure, in early 1971. It stiffened him in his bed. He slept face down, and the intake of breath pulled in a portion of the pillowcase. I'm sure he never knew what was happening. But as he gyrated on the bed, his legs kicking and quivering, the life went out of him, stuffed into submission by the bunched cloth in his throat. He choked to death as the seizure electrified his brain.

So, the two photographs of my father and son are on my desk, and I'm looking at them now as I write. My father was killed by a seizure. My son lives through seizures of every kind. Looking at these photos, I wonder what happens when convulsions seize the lives of those like me, who suffer no epilepsies at all.

____

(Part Three of this essay can be found here. Parts Four and Five can be found here.)