(Note: Parts One and Two of this five-part essay can be found here. Parts Four and Five can be found here. )

THREE : 1997

The silence and darkness around words interest me as much as the words themselves, the minuscule pauses between words, the long silences in which all of the language waits for a few of its words to be organized and chosen. The dark pool of wordplay lies there, and it is there that I find the beginning of the story. Everything is a story, whatever story: the quick joke over coffee, gruff disgruntlement, a daydream, a major novel. Style is the story. Plot is the story. Character. Birth. Suspense. Comedy. All these can be found in the pause, during which I’m trying to figure out what to write next.

Who taught me the most about this is my son Brennan.

For me, a state of gregarious chatter is the norm, something that comes from my family (Irish storytellers all, particularly my grandfather M.J. Brennan and his daughter, my mother Alice). This gabbiness has only been enhanced by my adult profession selling for large printing companies in San Francisco. Among the serious authors I know, this is a rarity. It is so even among those authors who aren't so serious. My business profession is simply a long conversation that really never ends, though luckily it's never been the sort of calling described by Charley at Willie Loman's graveside as one that is lived "way out there in the blue riding on a smile and a shoeshine."

It has featured reasonable amounts of embarrassment when some complex printing job gets delivered too late for the product-release press conference, or the colors, for some reason, come out wildly wrong. In my case there was a very notable firing by the owner of a company for which I had worked for fifteen years, a born-again Christian whose sense of moral guidance was somehow defeated in a moment of great, and unwarranted, anger with me. It was an awful day, in which I was escorted to my car on five minutes' notice after a decade and a half at the firm, in which my gregariousness had gotten the better of me, and I had talked my way into getting canned. The out-of-court settlement for wrongful termination was substantial.

But on the whole I've enjoyed my business profession. Not for me Edith Wharton's observation in The Custom of the Country that "a man doesn't know till he tries it how killing incongenial work is, and how it destroys the power of doing what one's fit for, even if there's time for both."

But it is true that business does not provide a contemplative life. Everything happens very quickly, with hectic, sometimes cantankerous or panic-stricken results, and there is little in business that feeds one's soul in any sort of way. It is life for the person of action. So I've always needed to find ways of providing myself with times of contemplative silence, so that I can write. I must be in a solitary frame of mind when I do that. I must be alone with my thoughts. So the very act of translating all the things I see in my business life into elements useful to, for example, the development of a particular character in a novel requires such solitude.

Although I needn't be physically alone, or even in a quiet place, when I write. My silences are internal to me, and are not dependent on actual place. One of the problems of being in business is that there is seldom time to write. So, I developed some time ago the ability to write anywhere, under almost any circumstances. I could write in the trenches if I had to. My book of stories The Day Nothing Happened was written at lunchtime, principally at the San Francisco Tennis Club. I had a dining room privilege there through the company for which I was working, and I had lunch in that place a good half of the days that it took me to write the book. But I also wrote elsewhere, surrounded by waiters, clattering dishes, and noisy lunchtime customers, at numberless tables for one, in most of the coffeehouses and restaurants in the South of Market neighborhood of San Francisco, between the waterfront and, approximately, Fifth Street.

All my books so far have been written under such circumstances.

I wrote those books longhand, and the words on the page reflect the haphazardness of the writing. My handwriting is, under the best of circumstances, illegible. It's as though I write my own oracular code, even though it's plain English. It's left to me to present myself to the desktop computer late at night, to interpret the handwritten runes for it. No one else could.

In the face of all this clatter, I've found the internal silences to be all-important. They represent a void that Thomas Moore in his fine book Care of the Soul says "evokes an awareness and articulation of thoughts otherwise hidden behind the screen of lighter moods." Melancholic darkness contains what we don't know yet or have not discovered, and is the source of art and language, the stuff that matters to me most.

For most of my life, I have not known this, and so have feared contemplation of such darkness. I turned away from it for many years, preferring to accept some sort of status quo, some formula determined for me by my family or by my own fear that stepping out of line was dangerous. As my father said so often in our conversations, "You shouldn't bother people with your problems. Keep them to yourself." For me now, after the startling production of a great deal of prose, that's another way of saying that you should not admit to the possibility of chance disaster, to the notion that the empty universe is really empty—or full—or that in silence and darkness lies the search for the new.

In other words, where art resides.

But for many years I too thought such things should be avoided, because they caused me to be afraid. Darkness and silence couldn't be quantified. You couldn't tell what they were, much less what they meant. No wonder my father saw them as problems. No wonder they terrified him.

During those conversations with my father, I would sit for an hour, sometimes two, late at night, bubbling with fury. I couldn't bear the conversations because they were so similar one after another, making my father appear to me foolish and fuddy-duddy. The conversations were also based on misinformation, because they painted such a glowing portrait of me and my accomplishments, when those assumed accomplishments really had little to do with the truth. What I wanted was for my father to depart from his formula and to imagine other possibilities, to commiserate with the difficulties I was having, or, more importantly, to be able to see what it was that I was trying to understand…just then for the first time in my life. The reading. Exploring dark fearfulness. The writing. Extracting some kind of expression from the sea of words. The exploration.

But I know that, for a couple of reasons, this was impossible for him. Darkness was the very opposite of what fueled my father's interest in living. He hated the contemplation of such things. Darkness meant unhappiness, dismay, bad behavior, all things negative. "I've got my own problems," he said to me hundreds of times, when I would be making an attempt to deepen the subject. Indeed, that phrase was one of the formulae that would bring the conversation directly back to where he had left it off, when I had interrupted.

So I would fume, resentful. I'd sit uncomplaining, listening again to an exact repetition of what I had heard him say to me the last time I'd come home from Berkeley, or perhaps to the same thing he had said to me the night before. I could not change it. I had too much respect for him to shout at him. I didn't know how to ask anyone else in the family if they had discerned the same kinds of things I was seeing, because my family doesn't pry. You were supposed to keep your troubles to yourself. So we didn't ask, because the truth would maybe require that one's troubles—my father's troubles—be spilled out for everyone to see, a fate we all thought was unbearable.

I came to feel like a volcano in a vault.

Now, though, I realize what it was like for my father. All he wanted was to tell his son how proud he was of him. I know that he had great respect for my achievements, especially since I had heard so often the story of his own hurried departure from the University of Arizona in 1929. As stolid and formulaic as that story was, it was always told regretfully, always sadly.

He was like Brennan, in that his search for expression, his wish for words to tell the story, encountered extreme difficulties. A lumpish fist was growing in his brain and muscling it out of the way. Some tumorous mass of listless and truly thoughtless gristle was making it impossible for him to seek new ways of talking, new ideas, new versions of things.

There is a symptom that accompanies some forms of severe epilepsies. It is called perseveration, and it features the monotonous repetition of words, sounds, and actions on the part of the patient. The patient will frequently get into patterns of speech that are almost exact, repetition to repetition.

It has been explained to me that perseveration can be anxiety-related, and is usually caused by a brain injury or other organic disorder. It is the source of much of Brennan' s repetitiveness. I'm not sure that my father's constant, circular conversation could be said to be the same direct result of his own brain injury. For one, each individual portion of his repetitive speech was hours long and quite complex, unlike my son's. But at least I'm certain that those monologues of his were caused by some symptom of his disease that surely resembled Brennan's.

When this idea entered my mind the first time, it came as a shock to me. I'd been complaining about and condemning my father's oddities for a very long time. I learned about this new possibility from my son's physicians after my father had been dead for more than ten years.

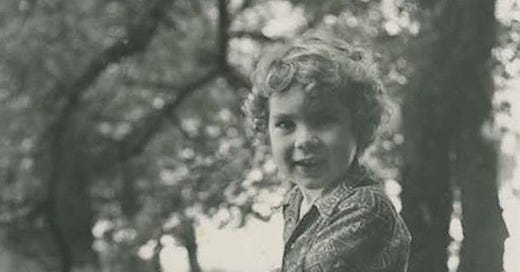

In 1975, at about the same time of the photograph of Brennan playing on the fence, I wrote a group of poems about him and his troubles. He was taking five anticonvulsants and having more than a half-dozen major seizures a day (one of which was in bed with us, first thing in the morning, almost every day. It was as though the transition from isolated sleep to the nesting arms of his parents changed the atmosphere, allowed his nerves to drop their guard, and ushered in the lightning strike).

There were only a few poems to him, about a half-dozen, that were included in my first book ever, The Englewood Readings, published by Len Fulton at Dustbooks in California. The proverbial slim volume of verse. In the chaos and pain of that time, one of the things that distressed me most was the silence that opened between Brennan and us in the midst of his attacks. There was nothing for Cathleen and me to do but watch him enter the embrace of the strange silence. There was no explanation. So it was left to us to ruminate about it, as we did hundreds of times.

(In these situations, the parents of such a child often consider the possibility that they have done wrong, that this child is God's punishment or some such. You succumb to this at your peril.)

The seizures were very quiet. Sometimes at the beginning he would cry out, a kind of guttural grunt that announced the release of all that undisciplined energy in his head. But more often, he just fell headlong into it, in silence. He'd be seized, literally, in a split-second, and his muscles would turn to taut strings, everything would straighten out, and he'd quiver, immovable, tossed to the ground.

In his teenage years, the bad seizures changed, so that he was no longer thrown down. Now, he can remain standing. He maintains his balance. But he is just as disappeared, beyond our reach just as much as ever. Also, now, when I take his hand or try to put my arm around him for comfort (he is, by the way, now more than six feet tall), he pushes me away, pushes my hands away, as though he doesn't want any help, as though to say, "Get away from me!" So he stands by himself, his face contorting, his arms shaking, in complete silence.

In all this epileptic silence, Brennan and I share some space somewhere, in quite different ways, but closely.

Now, in 1997, Brennan is twenty-six years old, and there are similar elements in our relationship to those described in the poems of that book, written when he was three. Conversations with him feature frequent repetition of large portions of previous conversations, and very long pauses during which Brennan is trying to figure out what he's going to say next. I've always thought that it's rude to finish sentences for him, even though I could do that for almost every sentence. I almost always know what he's going to say. It's part of his affliction that he repeats himself and that he has such trouble putting together his thoughts. So when one of the pauses comes, I wait.

Sometimes we sit for several minutes.

I think that one of the reasons for my patience is that I know how it is for Brennan. Like all other writers, I frequently sit and stare into some dull-seeming oblivion, apparently dumbfounded. But of course what we're doing is thinking about it. "If J. were to do this, what would that mean to M.'s uncle when he asks P. to run away with him to Islamabad?" Etc.

It would probably come as a surprise to most of my business clients to know that I am thinking all the time about what's going on in my writing, even in the midst of rapid-fire, complex, and heated business meetings. All the time. Because it's all in the pause, all in the darkness. I'm trying to force a word or two from the silence.

In Brennan's pauses, he too is in the dark pool of word play, although his choices apparently are much fewer than mine. His speech is the last word in realism. With many people who are brain-injured, abstract thought is not much of an option. The facts are what matter and what form the basis for any thoughtful consideration there is. So, to ask Brennan for a sensuous description of the foods he ate at dinner last night is to ask him for information he doesn't have.

"How was dinner, Brennan?"

"Good."

"What do you mean, 'good'?"

"The fish was good."

"How did it look?"

"Like fish."

He comes the closest, I believe, to leaving the facts and moving to things like metaphor when he talks about his personal relations and particularly about kindness. Since he has been an adult, Brennan's childhood kindness, which was constant and constantly remarked upon, has become part of a complex of other kinds of personal expression, like anger at his situation, self-interest, unwarranted disgruntlement with Cathleen and me, foolishness, humor mistaken by him for cruelty, wrong-minded misapprehension, and so on. That is, he's more like the rest of us now.

But when the subject of kindness in personal relations comes up, he can sometimes come close to waxing eloquent about it, even though it is often expressed in terms of an irritating self-congratulation.

Of course, the notion of "irritating self-congratulation" is one that Brennan does not understand, thus making helpful suggestions on my part that are intended to instruct him on how to behave a little better (every father's prerogative) into moments of comic uselessness.

Nonetheless, when he's in the middle of one of his long pauses, he is struggling to pull some kind of fact-driven utterance from it. When he falls into the silence, he has to do combat with the strange electrical misdeeds of his brain, which make the contemplative search even more difficult. In many respects, I think his visits to the silence are far more profound than mine, because his silences are interrupted by lightning. It's the lightning that dazzles him into repetition, which makes his choices for language appear like no choice at all. It's no wonder he seems stupefied so often in his search for words. He's being shot through with odd electric currents even as we sit quietly waiting.

So I wouldn't presume to interrupt and try to finish the sentence for him, because it would not only be a betrayal of his feelings, it would also be a betrayal of his personal struggle. Last of all, it would be a betrayal of the silence itself, the source of the story, of darkness, the attempt at language and communication.

_____

(Note: Parts One and Two of this five-part essay can be found here. Parts Four and Five can be found here. )